Adjusting wRVUs for Modifiers when Compensating Physicians: The How and the Why

The use of CPT code modifiers to adjust work relative value units (wRVUs) under physician compensation models has become a universal practice among hospitals and health systems that employ physicians—and with good reason. The risks of not applying CPT code modifiers—such as an inability to objectively measure performance—are significant.

Why should healthcare organizations that employ physicians use CPT code modifiers to assess physician work effort relative to benchmarks? There are a number of factors to consider.

WHY USE MODIFIERS TO ADJUST WRVUS?

wRVUs reflect the physician’s expertise as well as the time and technical skill spent performing the service, including the mental effort and judgment expended by the physician prior to, during, and after a patient encounter. Physician work relative values are updated each year to account for changes in medical practice.

While the resource-based relative value scale (RBRVS) system was developed as a mechanism to determine Medicare reimbursement levels, wRVUs have become an accepted metric for most physician compensation models. That’s because wRVUs offer a way to calculate both the volume of work and effort expended by a physician in treating patients.

Modifiers enable healthcare providers to submit additional information to the payer regarding the service provided. In general, modifiers indicate that the standard services or resources reflected in the reimbursement for a particular CPT code—determined in part by the wRVU level—have been modified.

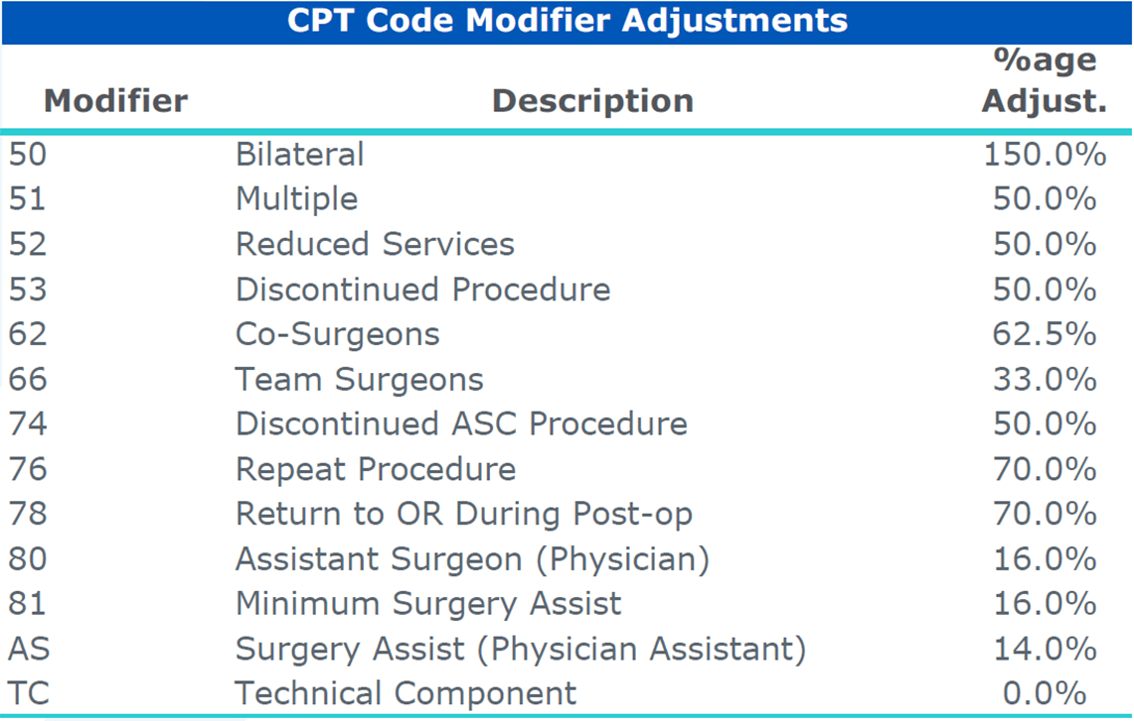

A modifier can either increase or decrease the wRVU value. Although actual modifier adjustments can vary among payers, the American Medical Group Association publishes a commonly accepted list of modifiers and their corresponding adjustment in its annual Medical Group Compensation and Productivity Survey, shown in the exhibit below.

EXHIBIT ONE:

Commonly Accepted CPT Code Modifiers and Adjustments: AMGA

HOW CPT MODIFIERS ARE APPLIED

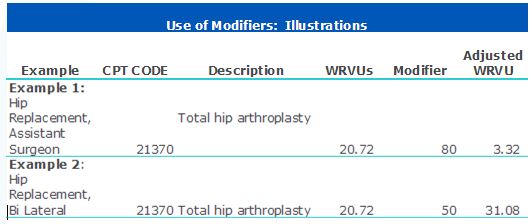

The exhibit below illustrates the impact of the use of a modifier on the wRVU value for a procedure.

EXHIBIT TWO:

How the Use of a CPT Modifier Changes the wRVU Value for a Procedure

In the first example, a modifier of “80″ attached to a surgical code indicates that the surgeon assisted another surgeon with the procedure. In this case, the wRVU value (and the resulting reimbursement) would be 16 percent of the value of the procedure. In other words, the primary surgeon would receive 20.72 wRVUs and the assistant surgeon would receive 3.32 wRVUs.

In the second example, the surgeon will receive 31.08 wRVUs for a bilateral hip replacement, reflecting the additional effort associated with a bilateral procedure. Note that the surgeon does not receive 41.44 wRVUs (20.72 wRVUs times two) because there are efficiencies in time and intensity gained from replacing two hips during the same surgery. In general, a surgical code provides for time and intensity before, during, and after the surgery, and the global codes reflect services provided for a 30-, 60-, or 90-day period.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PHYSICIAN COMPENSATION

Physician compensation surveys, such as those published by the Medical Group Management Association, AMGA, and Sullivan Cotter & Associates, Inc., typically report data that is adjusted to account for modifiers. These same surveys are also used to determine the “conversion factors” used in compensation plans. Use of unadjusted wRVUs in determining physician work effort can result in either overstating or understating physician work effort and, ultimately, compensation, creating a potential compliance concern.

Although the impact of modifiers in primary care specialties is relatively limited, the impact in surgical and/or procedural specialties can lead to a material difference in annual wRVUs (e.g., surgery, orthopedics, imaging, and gastroenterology).

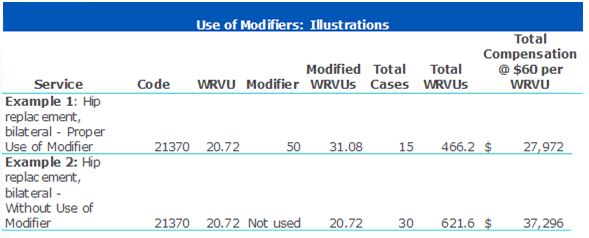

Furthermore, to the extent healthcare organizations rely upon wRVUs in their physician compensation model, there is a potential for overpayment. Consider a surgeon who is compensated $60 per wRVU. The surgeon performs 15 bilateral hip replacements. Table 2 indicates that hip replacements have a WRVU value of 20.72. Table 3 illustrates the impact on wRVUs and payment levels with and without the modifiers.

EXHIBIT THREE:

Comparing the Impact on wRVUs and Payment Levels With and Without Modifiers

Without a modifier adjustment, the surgeon would be credited with 621.6 wRVUs and earn $37,296. However, since the physician operated on both hips at the same time, a modifier of “50” should apply. Therefore, instead of receiving the full wRVU value for each hip, the wRVU value would equal 150 percent of the 31.08 wRVUs. The appropriate application of the CPT code modifier would result in actual cash compensation of $27,972.

This hypothetical example illustrates the potential danger associated with failing to properly account for CPT code modifiers in the context of a production-based compensation model.

THE NEED FOR A CAREFUL APPROACH

The widespread adoption of wRVUs in employed physician compensation models results from the perceived fairness of measuring physician productivity based on wRVUs. Use of wRVUs eliminates the impact of an organization’s payer mix and contracting leverage as well as any other inefficiencies in the billing and collecting process. Thus, while wRVU compensation models are not directly tied to practice collections, wRVUs themselves are used to measure work effort and determine both reimbursement and compensation levels.

Hospitals and health systems that employ physicians should appropriately account for CPT code modifiers to properly assess physician work effort relative to benchmarks. More important, those organizations with wRVU-based production elements in their compensation methodologies need to ensure appropriate application of CPT code modifiers in calculating wRVUs for purposes of determining physician cash compensation to avoid potential compliance issues. Failure to do so creates a potential risk of overpayment to a physician as well as a possible disconnect between the practice’s financial performance and physician cash compensation.